Therapeutic effects of kaempferol, quercetin and quinoa seed extract on high-fructose diet-induced hepatic and pancreatic alterations in diabetic rats

Published: 31 December 2024

Volume 3Abstract

Excess fructose intake is a main contributor to metabolic syndrome, which causes dyslipidemia, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and insulin resistance. The present study examined the protective effects of quercetin, quinoa seed extract (QSE), and kaempferol against high-fructose diet (HFrD)-induced pancreatic and hepatic alterations in Wistar albino rats. Thirty rats were divided into six groups (n = 5, each group consisted of 5 rats): the control group, HFrD + metformin group, HFrD + kaempferol group, HFrD + quercetin group, and HFrD + QSE group. Treatments were administered orally for 21 days following induction with 61% fructose. Biochemical function tests were performed for hemoglobin (Hb) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, and histopathological analyses of hepatic and pancreatic architecture were performed. The results showed that HFrD intake significantly increased ALT levels and body weight, accompanied by hepatocellular degeneration and inflammatory changes in pancreatic β-cells. Kaempferol, quercetin, and QSE administration significantly increased the Hb concentration, decreased ALT activity, and reduced vacuolar degeneration and hepatic necrosis. Kaempferol and quercetin resulted in nearly normal hepatocyte morphology among the test compounds, while QSE resulted in the greatest decrease in net weight gain. In the treated groups, pancreatic sections revealed the integrity of the islets of Langerhans and decreased inflammation of the islets. This study demonstrated that flavonoids from plants and the QSE have hepatoprotective and pancreatic protective effects through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms; hence, these compounds are potentially useful as therapeutic agents in the management of fructose-induced metabolic dysfunctions.

Keywords

Kaempferol; Quinoa seed extract; Quercetin; Pancreatic and pancreatic protection; High-fructose diet

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome, a medical condition worldwide, is generally associated with diabetes mellitus (DM), insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and increased triglyceride and cholesterol levels, which are often accompanied by liver and pancreas dysfunction [1]. Excessive fructose intake is one of the contributing factors to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). High fructose intake causes oxidative stress and inflammation in pancreatic beta cells, leading to impaired insulin production and secretion, thus causing hyperglycemia [2]. Excess fructose intake contributes to visceral adipose deposition and hepatic steatosis to promote the production of inflammatory mediators, increasing the risk of chronic diseases such as T2DM and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [3]. NAFLD, a disease characterized by fat deposition on hepatocytes, is associated with an abnormal lipid profile, including low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high cholesterol levels [4]. Biomarkers such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) increase due to hepatocellular injury. Chronic fructose consumption significantly contributes to cirrhosis, hypertriglyceridemia and NAFLD [5].

Pakistan ranks third in the world in terms of diabetes prevalence, followed by China and India. The national prevalence of diabetes has consistently increased over recent years, increasing from 11.77% in 2016 to 16.98% in 2018 and 17.1% in 2019 [6]. According to the latest International Diabetes Foundation (IDF) atlas in 2023, approximately 33 million adults are living with T2DM in Pakistan, making it the third-largest population with diabetes in the world. In addition, approximately 11 million adults have impaired glucose tolerance, placing them at high risk of progression to diabetes, whereas approximately 8.9 million people with diabetes are still undiagnosed [7]. The variability in the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in Pakistani people is also reflected by its wide range, ranging from 4.41% to 57.90%, across different studies [8].

The therapeutic potential of medicinal plants has gained increased scientific attention. Bioactive plant constituents such as kaempferol have shown beneficial effects on hypertension, pancreatic disorders, and DM [9]. Flavonoids are naturally occurring polyphenolic compounds that are widely distributed among vegetables and fruits, including radish, parsley, grains, oregano, leafy greens, and citrus fruits such as oligomers, aglycones and glucosides [10]. Glucosides include quercetin, naringin, kaempferol, and hesperidin [11].

Among these, the most powerful hepatoprotective and antidiabetic properties are exhibited by kaempferol and quercetin. Quercetin is involved in reducing pancreatic inflammation, which moderates Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT-1) expression to increase fatty acid oxidation, thereby reducing NAFLD progression [12]. Kaempferol stabilizes normal liver function by inhibiting inflammatory mediators and reducing hepatic triglyceride accumulation through the downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) and sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (SREBP-1) [13]. Quercetin offers further protective benefits against metabolic syndrome, liver cancer, and cardiovascular disease by suppressing NF-κB activation and reducing the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1α [14,15]. Flavonoids have been demonstrated to be effective antidiabetic therapeutic agents because they protect pancreatic beta-cell integrity and support glucose homeostasis. In type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), autoimmune beta-cell destruction results in high blood sugar levels, whereas long-standing insulin resistance contributes to T2DM [16]. Kaempferol and quercetin protect beta cells from apoptosis. Kaempferol has been shown to specifically inhibit the activity of caspase-3 [17].

Chenopodium quinoa Willd. (Chenopodiaceae) consists of approximately 250 species that are spread all over the world. Owing to its gluten-free nature, quinoa is consumed by patients suffering from celiac disease and is considered highly nutritious. Quinoa seed extract (QSE) includes various flavanols, such as kaempferol glycosides, apigenin and quercetin [18]. QSE improves the lipid profile, mineral balance, protein metabolism, and blood glucose regulation [19]. It has been shown to lower total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL, blood sugar, and circulating protein levels [20]. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the effects of standard therapy (metformin) and natural compounds (quercetin, kaempferol, and QSE) on metabolic syndrome and to evaluate the protective effects of these compounds against high-fructose diet (HFrD)-induced hepatic and pancreatic alterations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and approval

This experimental study was approved by the Directorate of Graduate Studies, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad (No. 5738-27/DGS). The study was based on an animal model; young albino Wistar rats were obtained from Government College University, Faisalabad, and the study was conducted at the Institute of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan.

2.2. Selection of drugs

Kaempferol and quercetin were selected as representative pure flavonoids because of their well-documented antidiabetic, antioxidant, and hepatoprotective activities, including the modulation of insulin signaling, lipid metabolism, and pancreatic β-cell protection [21,22]. QSE was included to assess the synergistic effects of multiple phytochemicals naturally present in quinoa, particularly kaempferol and quercetin glycosides, which may act additively or synergistically to enhance therapeutic outcomes [23]. The comparative evaluation of these pure compounds and a whole-plant extract allow a broader assessment of both isolated bioactive molecules and complex phytochemical mixtures in mitigating high-fructose diet (HFrD)-induced hepatic and pancreatic alterations.

2.3. Collection of drugs and chemicals

All the compounds were prepared in vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 250 µL) diluted with 60% distilled water for administration. Metformin (chemical formula C₄H₁₁N₅, molar mass ~129.1 g/mol) is a first-line medication for T2DM and was obtained commercially under the name Glucophage. Quercetin and kaempferol were obtained from commercial sources [24]. Quinoa seeds were sourced and extracted via standard solvent extraction methods [25]. D-fructose (Sigma–Aldrich) was purchased to induce HFrD.

2.4. Experimental grouping

This study involved 30 albino Wistar rats weighing 150–200 grams. Thirty rats were divided into 6 groups (n = 5 per group). Group 1 served as the control group and was given a standard diet. Group 2 served as the disease model (HFrD 61% only). Group 3 received HFrD + metformin (M) (HFrD + M, 61% fructose + 100 mg/kg body weight, orally). Group 4 received HFrD + kaempferol (K) (HFrD + K, 61% fructose + 100 mg/kg). Group 5 received HFrD + quercetin (Q) (HFrD + Q, 61% fructose + 100 mg/kg). Group 6 received HFrD + QSE (HFrD + QSE, 61% fructose + 200 mg/kg). All the treatments were given orally.

2.5. Administration of drugs

In the first week of the study, a HFrD was given to all the groups except the control group (which was fed a normal diet and received no treatment). Drug administration was initiated in the second week. Kaempferol, quercetin, and QSE were administered to the respective treatment groups (HFrD + K, HFrD + Q, and HFrD + QSE) via oral gavage for 3 weeks. All the compounds were delivered in 250 µL of DMSO diluted with 60% distilled water. The treatments were given daily, and the experiment lasted a total of 28 days. The body weights of all the rats were measured daily throughout the 28 days. On day 29 of the trial, the animals were euthanized for sample collection; blood samples and liver and pancreas organs were collected from all 6 groups in accordance with ethical guidelines.

2.6. Data collection procedure

The rats were anesthetized via the inhalation of chloroform via cotton swabs. Under deep anesthesia, an incision was made in the left jugular vein to collect a blood sample (~2 mL) in an EDTA vial for complete blood count (CBC) analysis. The remaining blood was collected into clot activator (red-top) tubes to obtain serum for biochemical analyses [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and AST levels]. After dissection, the liver and pancreas from each rat were harvested and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for preservation.

2.7. Histopathological analysis

Liver and pancreas tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and then processed through graded ethanol for dehydration. Xylene was used to clear the tissues, which were then embedded in paraffin wax. Five-micrometer-thick sections were cut via a microtome. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed following standard protocols. The stained sections were mounted and examined via light microscopy for histopathological changes.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics [mean ± standard error (SE)] were calculated for body weight, white blood cell (WBC) count, and hemoglobin (Hb), ALT, and AST levels for each group via SPSS version 24.00.

3. Results

Table 1 shows that the terminal average weight of all six groups was greater than the initial average weight. Minimal weight gain was observed in all groups during the first week; however, weight increased in the second week and continued to rise throughout the trial. The groups receiving kaempferol, quercetin, or QSE gained less body weight than the untreated HFrD group did. Moreover, the HFrD + QSE group presented the lowest net weight gain over the course of the experiment. Compared with the control group, the HFrD group presented the greatest weight gain, whereas the HFrD + QSE group presented the smallest weight gain.

| Days | Control | HFrD | HFrD + M | HFrD + K | HFrD + Q | HFrD + QSE |

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | |

| 1st Week | ||||||

| 1 | 175.4 ± 1.2 | 186.8 ± 1.4 | 183.0 ± 0.5 | 174.2 ± 0.6 | 156.8 ± 0.5 | 203.6 ± 1.7 |

| 2 | 174.6 ± 1.1 | 185.6 ± 1.4 | 183.2 ± 0.5 | 175.6 ± 0.6 | 152.0 ± 0.5 | 194.2 ± 1.7 |

| 3 | 178.0 ± 1.1 | 186.2 ± 1.4 | 184.8 ± 0.6 | 177.0 ± 0.6 | 158.4 ± 0.5 | 197.2 ± 1.7 |

| 4 | 178.8 ± 1.1 | 186.0 ± 1.4 | 189.0 ± 0.7 | 178.2 ± 0.6 | 161.4 ± 0.5 | 195.2 ± 1.6 |

| 5 | 180.4 ± 1.1 | 188.4 ± 1.4 | 191.2 ± 0.6 | 179.8 ± 0.6 | 164.0 ± 0.5 | 197.6 ± 1.6 |

| 6 | 179.4 ± 1.0 | 188.0 ± 1.4 | 191.6 ± 0.6 | 180.4 ± 0.7 | 165.4 ± 0.5 | 199.2 ± 1.6 |

| 7 | 180.6 ± 1.0 | 184.8 ± 1.4 | 187.8 ± 0.6 | 184.2 ± 0.6 | 163.8 ± 0.5 | 197.8 ± 1.8 |

| 2nd Week |

||||||

| 8 | 188.6 ± 0.9 | 186.6 ± 1.4 | 192.0 ± 0.6 | 183.8 ± 0.6 | 163.8 ± 0.5 | 194.8 ± 1.7 |

| 9 | 194.0 ± 0.8 | 204.4 ± 1.3 | 205.6 ± 0.6 | 199.6 ± 0.7 | 188.0 ± 0.4 | 210.6 ± 1.7 |

| 10 | 185.2 ± 0.9 | 186.2 ± 1.4 | 196.0 ± 0.6 | 183.6 ± 0.6 | 171.8 ± 0.4 | 202.4 ± 1.7 |

| 11 | 187.4 ± 0.8 | 190.8 ± 1.4 | 200.2 ± 0.7 | 186.8 ± 0.6 | 182.8 ± 0.5 | 203.4 ± 1.7 |

| 12 | 196.4 ± 0.8 | 202.8 ± 1.3 | 193.8 ± 1.1 | 194.6 ± 0.7 | 186.8 ± 0.4 | 209.4 ± 1.6 |

| 13 | 194.0 ± 0.8 | 204.4 ± 1.3 | 205.6 ± 0.6 | 199.6 ± 0.7 | 188.0 ± 0.4 | 210.6 ± 1.7 |

| 14 | 196.8 ± 0.7 | 212.2 ± 1.2 | 210.6 ± 0.6 | 213.0 ± 0.6 | 190.0 ± 0.4 | 213.0 ± 1.5 |

| 3rd Week |

||||||

| 15 | 197.6 ± 0.7 | 210.0 ± 1.2 | 212.2 ± 0.6 | 216.6 ± 0.6 | 189.4 ± 0.5 | 222.6 ± 1.5 |

| 16 | 205.0 ± 0.7 | 211.0 ± 1.1 | 208.2 ± 0.7 | 217.4 ± 0.6 | 189.2 ± 0.4 | 219.6 ± 1.5 |

| 17 | 208.6 ± 0.7 | 216.2 ± 1.3 | 210.0 ± 0.7 | 212.0 ± 0.6 | 188.6 ± 0.5 | 228.2 ± 1.6 |

| 18 | 209.2 ± 0.7 | 215.8 ± 1.2 | 210.2 ± 0.6 | 208.8 ± 0.6 | 192.2 ± 0.5 | 227.4 ± 1.5 |

| 19 | 209.8 ± 0.7 | 216.8 ± 1.3 | 211.4 ± 0.6 | 210.4 ± 0.6 | 194.4 ± 0.5 | 229.6 ± 1.5 |

| 20 | 209.0 ± 0.7 | 235.0 ± 1.1 | 218.6 ± 0.6 | 224.8 ± 0.3 | 192.8 ± 0.5 | 239.6 ± 1.6 |

| 21 | 210.4 ± 0.7 | 234.8 ± 1.2 | 217.6 ± 0.6 | 219.4 ± 0.5 | 191.4 ± 0.5 | 238.2 ± 1.6 |

| 4th Week | ||||||

| 22 | 214.2 ± 0.7 | 239.6 ± 1.2 | 219.2 ± 0.6 | 220.0 ± 0.6 | 199.4 ± 0.6 | 240.4 ± 1.6 |

| 23 | 216.0 ± 0.7 | 244.8 ± 1.2 | 222.6 ± 0.6 | 217.6 ± 0.5 | 198.2 ± 0.6 | 240.8 ± 1.6 |

| 24 | 216.0 ± 0.7 | 245.4 ± 1.2 | 222.8 ± 0.6 | 217.6 ± 0.5 | 198.8 ± 0.6 | 241.4 ± 1.6 |

| 25 | 216.8 ± 0.7 | 245.6 ± 1.2 | 223.0 ± 0.6 | 218.0 ± 0.5 | 199.4 ± 0.6 | 242.0 ± 1.6 |

| 26 | 218.6 ± 0.6 | 237.2 ± 1.2 | 221.6 ± 0.6 | 212.4 ± 0.6 | 198.4 ± 0.6 | 241.6 ± 1.6 |

| 27 | 219.8 ± 0.6 | 231.2 ± 1.2 | 220.8 ± 0.5 | 212.0 ± 0.6 | 200.6 ± 0.6 | 238.6 ± 1.6 |

| 28 | 219.2 ± 0.6 | 231.8 ± 1.1 | 218.0 ± 0.5 | 213.2 ± 0.6 | 199.0 ± 0.5 | 234.0 ± 1.5 |

| Abbreviations: HFrD, high-fructose diet; M, metformin; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; QSE, quinoa seed extract. | ||||||

Compared with the control group, the HFrD group presented a mild increase in leukocyte count, with an average of 11.98 ± 2.97 × 10³/µL, with an average of 9.80 ± 1.13 × 10³/µL. These findings suggest that systemic inflammation coexists with metabolic stress (Table 2). Moreover, Hb concentrations were slightly lower in the HFrD group, with an average of 147.73±23.80 g/L, than in the control group, which was 154.07 ± 9.85 g/L. This reduction in Hb and leukocyte levels is consistent with anemia observed in DIDM (diet-induced diabetic models). Furthermore, the markers of liver function were significantly greater in the HFrD group; ALT and AST increased to 104.41 ± 31.04 U/L and 75.02 ± 13.93 U/L, respectively. The values for ALT and AST in the control group were 71.25 ± 10.54 U/L and 68.03 ± 6.46 U/L, respectively. These increases reflect hepatocellular damage due to excess fructose.

Quercetin (HFrD + Q) and kaempferol (HFrD + K) treatment significantly diminished these abnormalities. Both flavonoids resulted in ALT and AST levels close to normal, with ALT values recorded at 64.30 ± 9.14 U/L for HFrD + K and 64.41 ± 13.81 U/L for HFrD + Q and AST values of 59.26 ± 4.09 U/L for HFrD + K and 60.49 ± 9.70 U/L for HFrD + Q. These findings indicate that the effective hepatoprotective actions of these compounds occur through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms. Additionally, the Hb levels showed partial recovery, measuring 126.93 ± 31.18 g/L in the HFrD + K group and 142.53 ± 22.10 g/L in the HFrD + Q group. The group that received HFrD + QSE (quinoa seed extract) presented similar trends, with progress in enzymatic and hematological profiles. Specifically, the Hb level was 113.20 ± 62.50 g/L, the ALT level was 88.22 ± 28.25 U/L, and the AST level was 57.46 ± 4.52 U/L. These results revealed the micronutrient and antioxidant benefits of the QSE matrix. Comparable stabilization was attained by treatment with metformin (HFrD + M), confirming a response to therapy in this model.

| Groups | WBCs (×10^3/µL) | Hb (g/L) | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) |

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | |

| Control | 9.80 ± 1.13 | 154.07 ± 9.85 | 71.25 ± 10.54 | 68.03 ± 6.46 |

| HFrD | 11.98 ± 2.97 | 147.73 ± 23.80 | 104.41 ± 31.04 | 75.02 ± 13.93 |

| HFrD + M | 9.36 ± 2.64 | 134.67 ± 11.16 | 87.84 ± 40.82 | 65.40 ± 14.59 |

| HFrD + K | 13.20 ± 2.26 | 126.93 ± 31.18 | 64.30 ± 9.14 | 59.26 ± 4.09 |

| HFrD + Q | 10.50 ± 3.16 | 142.53 ± 22.10 | 64.41 ± 13.81 | 60.49 ± 9.70 |

| HFrD + QSE | 11.18 ± 1.59 | 113.20 ± 62.50 | 88.22 ± 28.25 | 57.46 ± 4.52 |

| Abbreviations: Hb = hemoglobin; HFrD, high-fructose diet; M, metformin; K, kaempferol; Q, quercetin; QSE, quinoa seed extract. | ||||

Microscopic examination of the tissue slides revealed that hepatocytes in the control group appeared nearly normal, with a typical arrangement of hepatic cords (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Histopathological analysis of livers from the control group (a), HFrD group (b), kaempferol-treated group (c), quercetin-treated group (d), and QSE-treated group (e).

In contrast, the HFrD group presented signs of vacuolar degeneration in hepatocytes, dilated central veins and sinusoids, and hepatocellular necrosis. However, the groups treated with kaempferol, quercetin, or QSE along with HFrD presented only mild vacuolar degeneration, along with some dilated sinusoids and central veins, indicating the therapeutic effects of these plant flavonoids against HFrD-induced hepatotoxicity. Focal hepatic lesions (degeneration and necrosis with infiltration of WBCs) were observed in the HFrD group but were markedly reduced in the treated groups.

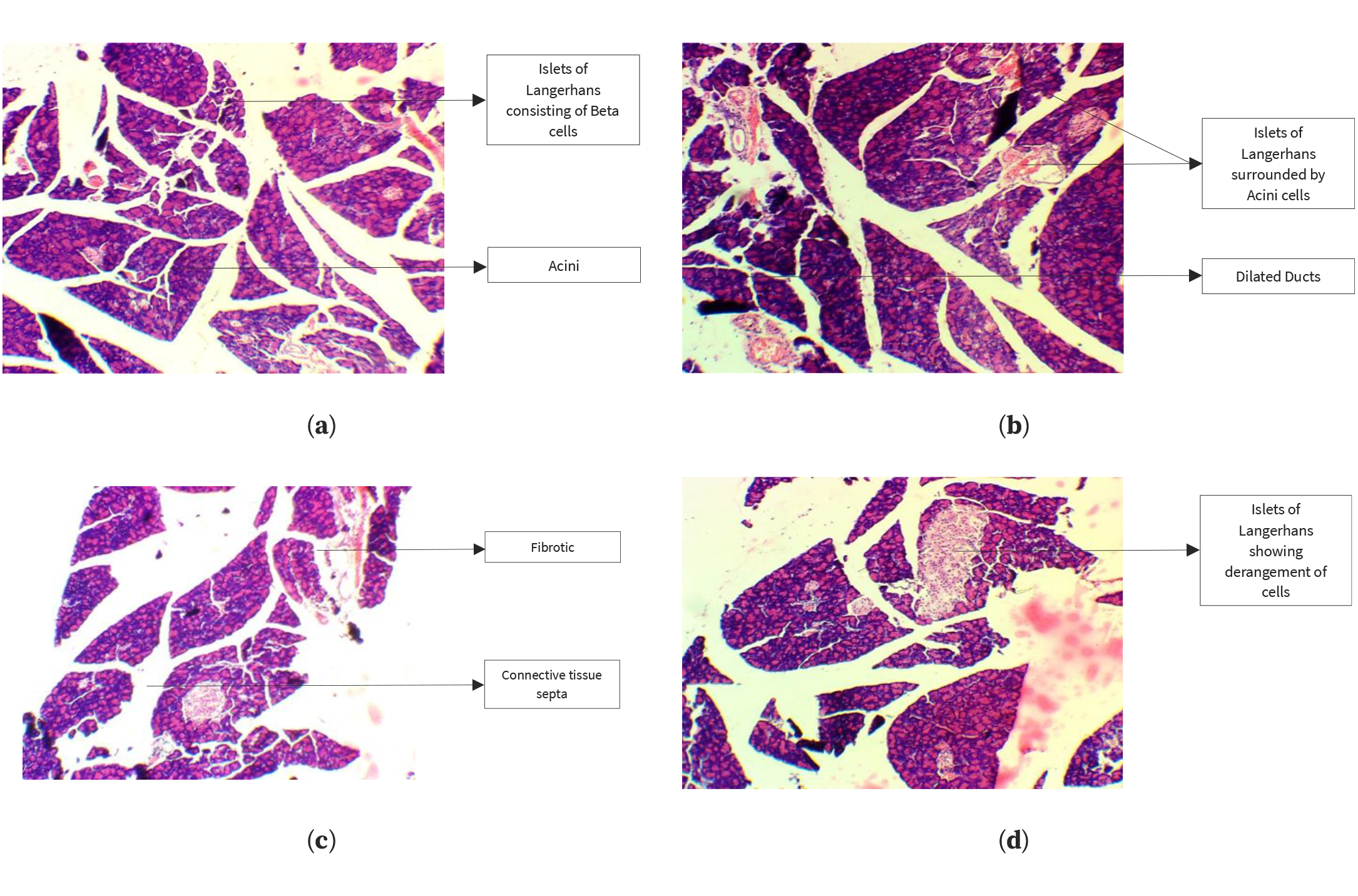

Histopathological analysis of pancreatic tissue samples revealed that the control group exhibited a normal arrangement of beta cells within the islets of Langerhans (Figure 2). In contrast, the HFrD group displayed inflammation of beta cells and abnormal enlargement of the islets, along with edema and dilated blood vessels in the pancreatic tissue. However, these adverse effects were reversed in the groups treated with kaempferol, quercetin, or QSE, with the pancreatic islet architecture preserved and reduced signs of inflammation and degeneration, thereby mitigating the metabolic disorders and pancreatic damage caused by HFrD.

Figure 2. Histopathological analysis of the pancreas in the control group (a), HFrD group (b), kaempferol-treated group (c), and quercetin-treated group (d).

4. Discussion

Taken together, all the treated groups showed a protective trend in comparison with the HFrD-untreated group. Body weight increased progressively in all groups during the experimental period, but its magnitude of increase was significantly lower in the groups receiving kaempferol, quercetin, or QSE, with the lowest net increase being observed in the HFrD + QSE group. Systemic metabolic stress due to HFrD feeding resulted in decreased Hb levels in rats in the HFrD group, while partial recovery of its concentration was observed in the treatment groups, suggesting partial correction of metabolic imbalance. Serum ALT activity, an important biomarker of hepatocellular injury, was highly elevated in HFrD rats, while the administration of kaempferol, quercetin, or QSE resulted in a remarkable reduction in ALT levels in these groups of rats and, in some instances, a decrease in ALT levels compared with the respective control values. Histopathological examinations further confirmed the above biochemical observations. HFrD exposure resulted in vacuolar degeneration, hepatocellular necrosis and inflammatory infiltration in liver tissues, whereas the treated groups exhibited only mild degenerative changes in the hepatic tissues with preserved architecture of the liver. Similarly, tissues of the pancreas obtained from diabetic rats fed a showed inflammation of the islets of Langerhans, disruption of β-cells, and edema, whereas those in the treatment groups maintained a normal islet morphology with fewer inflammatory changes. Overall, these observations suggested that quercetin, kaempferol, and QSE had significant pancreatic protective effects by decreasing fructose-induced structural and metabolic changes in diabetic rats.

Several studies have reported that flavonoids attenuate diet-induced weight gain. Kaempferol supplementation reduces weight gain and adiposity in rodent models by modulating the gut microbiota, increasing energy expenditure and improving insulin sensitivity, which is consistent with our observation of lower net weight gain in kaempferol-treated rats [26,27]. Quercetin has repeatedly been shown to blunt body weight gain in high-fat or fructose feeding regimens by reducing adipogenesis and increasing fatty acid oxidation (AMPK/SIRT1 pathways), which supports our quercetin group’s reduced weight gain relative to that of untreated HFrD animals [28,29]. Studies of quinoa or quinoa-derived extracts report reductions in weight gain or adiposity or improvements in metabolic indices versus obesogenic diets; these effects are attributed to combined polyphenol, fiber and protein contents, which can modulate satiety, lipid metabolism and the gut microbiota, which is compatible with our finding that QSE produces the smallest net weight gain [30,31].

Chronic high-fructose diets have been linked to dysregulated iron metabolism and systemic inflammation in animal models, which can manifest as reduced Hb or altered iron handling; one study of prolonged fructose exposure described inflammation-linked dysregulation of iron homeostasis in rats, providing a plausible mechanism for reduced Hb after HFrD [32]. Oxidative damage to erythrocytes under metabolic stress (high fructose/NAFLD) has been documented; antioxidants such as quercetin reduce erythrocyte oxidative markers and protect membrane integrity, which can help preserve Hb concentration or reduce hemolysis—this aligns with the partial Hb recovery observed in flavonoid-treated groups [33]. Reviews of red blood cell (RBC) redox biology emphasize that systemic metabolic stressors (lipid peroxidation, inflammation) impair RBC antioxidant systems and may lower Hb indirectly; interventions that restore redox balance can partially reverse these effects [34].

HFrD (and combined high-fat/high-fructose diets) consistently increase transaminase and liver injury marker levels in rodents and are widely used to model NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH); this finding replicates the marked ALT elevation observed in the HFrD group [35]. Multiple recent preclinical reports have shown strong hepatoprotective effects of quercetin, with reductions in ALT/AST, improvements in histology, and normalization of lipid metabolism attributed to antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and autophagy-promoting actions (AMPK/mitophagy pathways), which is consistent with our quercetin group’s ALT normalization [36]. Kaempferol has been shown to reduce ALT and attenuate hepatic inflammation in NASH and chemical injury models (e.g., suppression of the NLRP3 inflammasome/caspase-3 pathway), which is consistent with the pronounced decrease in ALT observed in the kaempferol group [37].

Diets high in fructose cause hepatic steatosis and inflammatory and advanced levels of necrosis and fibrosis; the histological patterns you observed are typical of HFrD models and have been reproduced in multiple recent studies [38]. Quercetin treatment reduces lipid droplet accumulation, hepatocyte ballooning and inflammatory cell infiltration in NAFLD models; mechanistic studies have revealed reduced SREBP-1c/fatty acid synthase expression (FASN) expression, increased PPARα-mediated β-oxidation, and improved mitochondrial function/mitophagy, which aligns with improvements in histology [36]. Kaempferol has been shown to decrease lipid accumulation, oxidative damage and inflammatory signaling in the liver, including histological amelioration in NASH models (reduced steatosis and necrosis), supporting the protective effects of kaempferol [26,37,39].

High-fructose feeding leads to systemic insulin resistance, β-cell stress and, in some models, β-cell dysfunction and islet inflammation; several animal studies have shown islet hypertrophy/hyperplasia or inflammatory changes in response to prolonged dietary sugar overload, which is consistent with the histology of the HFrD group [35,40]. Quercetin protects pancreatic β-cells from oxidative stress and apoptosis via the activation of Sirt3 and other antioxidant pathways, reducing cytokine-induced damage and preserving insulin secretion capacity—these findings align with the preserved islet morphology observed in the quercetin group [33,41]. Kaempferol stimulates autophagy, mitigates β-cell lipotoxicity via AMPK/mTOR signaling and supports β-cell survival in diabetic models; recent mechanistic and metabolomic studies reported that kaempferol improved islet histology and function, which is consistent with our kaempferol group’s ability to preserve islets [38,39].

The main strength of the current study is its controlled experimental design, which allowed the investigation of pancreatic and hepatic changes via biochemical markers as well as comprehensive tissue examination. A comparable evaluation of two pure flavonoids with a natural extract provides a practical basis for comparing their therapeutic potential. The use of valid biomarkers, such as AST and ALT, and standardized histological scoring in the current study also increases the confidence of the results. However, these experiments were conducted with relatively few animals, and the animal model was unable to fully represent the multiple inflammatory and metabolic mechanisms linked with human diabetes. In addition, single-dose regimens for each compound were adopted, and no attempt was made to understand dose‒response relationships. Moreover, no advanced statistics are employed in the study. Larger sample sizes, multiple dosing schemes, and mechanistic analyses at the molecular level are needed in future studies to increase the translational relevance of these findings.

5. Conclusions

QSE, quercetin and kaempferol can mitigate the pancreatic and hepatic changes induced in high-fructose diet-fed diabetic rats by improving biochemical markers, preserving tissue architecture, and reducing degenerative and inflammatory changes. The benefits observed in this model are very likely mediated through antioxidant pathways and metabolic regulatory pathways. In general, the results suggest that these bioactive phytochemicals represent potential therapeutic approaches as complementary agents in the prevention or management of diabetes-related hepatic-pancreatic dysfunction.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, SJ, AT, and JAK; methodology, SJ, and AT; software, SJ, and AT; validation, AT; formal analysis, SJ; investigation, SJ, and AT; resources, SJ, and JAK; data curation, SJ; writing—original draft preparation, SJ, and AT; writing—review and editing, SJ, AT, and JAK; visualization, AT; supervision, JAK; project administration, JAK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Publication history

| Received | Revised | Accepted | Published |

| 15 October 2024 | 17 December 2024 | 24 December 2024 | 31 December 2024 |

Funding

This research received no specific grant from the public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Directorate of Graduate Studies, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad (No. 5738-27/DGS).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author, Aisha Tahir, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Copyright

© 2024 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) License. The use, distribution, or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Publisher's note

Logixs Journals remains neutral concerning jurisdictional claims in its published subject matter, including maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Novoselova EG, Lunin SM, Khrenov MO, Glushkova OV, Novoselova TV, Parfenyuk SB. Pancreas β-cells in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: cell death, oxidative stress and immune regulation. Recently appearing changes in diabetes consequences. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2024;58(2):144-55. https://doi.org/10.33594/000000690